The following is a post sponsored by Dockers. Check out The Dockers Alpha khaki, the first of its kind. Grab a pair today and be the first to wear the next generation of khaki! Buy Now What’s this?

In September of 1914, Anglo-Irish explorer Ernest Shackleton set out on the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition with the goal of being the first man to traverse the Antarctic continent. Aboard what would become his aptly-named ship, the Endurance, he and 27 men set sail for the South Pole. But along the way, the ship became trapped in ice, setting off a series of events that would lead him away from his original goal and yet test him as a man and enshrine him as a hero far more than the attainment of it would have. While he did not complete the transcontinental journey he had hoped for, he brought back all 27 of his men alive, a feat of magnificent leadership without parallel.

How did he do it? Shackleton’s leadership abilities were myriad, but today we will focus on the two most vital: his resilience and service.

A Leader Must Be Supremely Resilient

Resiliency involves both the hardihood and courage to take on risks and challenges, and the ability to bounce back from difficulties and disappointments. Shackleton would face hardships that almost defy belief, and it was his iron-clad resilience that allowed he and his men to survive.

The story of the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition is the story of surging optimism met with crushing defeat manifested over and over and over again. That the former never failed Shackleton, and the latter never broke him, is truly what brought his men through to the other side.

Numerous times, Shackleton and his men felt incredibly hopeful that a goal was in sight and things were turning their way, only to have these hopes utterly dashed:

The Endurance trapped in ice.

- The Endurance gets stuck in the ice floes before reaching Vahsel Bay, where the expedition across Antarctica was to begin. But Shackleton is still hopeful that if they wait until the ice melts in the spring, they’ll be able to continue the journey.

- But after months trapped in ice, the pressure from the shifting floes twists and breaks the ships; it slowly fills with water and Shackleton must issue the order to abandon the vessel. The men must now camp on the ice floe.

The men attempt to pull the boats across the ice floes.

- Shackleton is hopeful that the men and dogs can pull the supplies and boats across the ice floes until they reach open water, at which point they can set sail for Paulet Island, 346 miles to the northwest. He leads the party, breaking the trail and trying to smooth the pressure ridges with a shovel and pick. But the wet snow soaks the men’s tents and sleeping bags and slows progress considerably. After only making it two miles in two days of marching, the plan is abandoned. The men will have to remain camped on a barren sheet of ice, where they must be careful that the ice does not crack and the killer whales do not rise to the surface and tip them into the freezing waters.

- After 2 months camped on the ice, Shackleton decides to attempt another march. The men once more leave in high spirits, but again, the progress is so painfully slow that the expedition is quickly abandoned. The men will have to camp for four more months as their icy home drifts for hundreds of miles, their lives completely at the mercy of nature. At one point, the coast of Antarctica comes within sight, but the way is blocked by ice, and Shackleton is forced to slowly slide away from his goal.

- After almost six months of living on ice, it finally melts sufficiently for the boats to be launched. The men set off for Elephant Island, which is only 30 miles away. After an arduous day of sailing, Shackleton feels hopeful they are almost there. But when their position is checked, they find they are now 60 miles from their destination—the current has carried them off course.

En route to Elephant Island the men first tried camping on ice floes, but this was abandoned when one cracked open as the men slept, tearing a tent apart and dropping its inhabitant, still inside his sleeping bag, into the icy waters. Shackleton, ever vigilant about the safety of his men, had sensed something was wrong, and was right on the scene, immediately fishing the man out.

- For seven days, Shackleton and his men row and sail in small, open boats upon the stormy seas. Blocks of ice threaten their path. Rain and snow squalls soak them though. Snow showers dust them in white. The sun is absent for 17 hours a day, and the temperatures dip below zero in the dark. Sleep comes only in tiny, involuntary snatches, and the men are completely exhausted. On the fourth day of the journey, the water supply runs out and the men grow so dehydrated they cannot eat. Elephant Island is spotted, but as they pull close, a strong gale prevents them from landing. For two days they can see their goal but not approach it.

- When the men finally make land, they dance along the “beach” and let the pebbles dribble through their hands. Despite the fact this was “an inhospitable place, devoid of any vegetation, covered with glaciers and swept by ice laden surges of the South Atlantic Ocean,” the men are overjoyed; this is the first time they’ve been on solid land in 497 days. But Shackleton realizes that their landing spot is too open to wind and waves, and the men must get back in the boats and move another 7 miles around the island.

- The men make camp and are greatly relieved, believing they will be able to spend the winter on the island and be picked up by whalers in the spring. But Shackleton realizes there will not be enough food on the island to last that long; he must break the news to the men and get back in the boat to sail another 800 miles to the whaling stations on the island of South Georgia.

The launch of the 22-foot James Caird from Elephant Island, the boat that would carry Shackleton 800 miles on the open sea to South Georgia.

- Shackleton chooses five men to accompany him, loads a boat with a month’s supply of rations, and takes off to their last hope of salvation. South Georgia was only a tiny speck of an island, and with the smallest mistake in navigation, the men would be swept out into the Atlantic Ocean, where the nearest land was thousands of miles away. For 16 days, the men are battered by waves and wind, fierce gales, and the constant spray of freezing ocean water, which chills them to the very marrow of their bones. Water makes its way into nearly every nook in the boat, including their moldering sleeping bags, and has to be continually pumped and bailed out by hand. The men cannot stand or sit up straight, and with the ship violently pitching back and forth, they must crawl over the stones serving as ballast to move from one part of the boat to another. Their bodies grow sore and bruised; exposure leaves their mouths cracked and swollen. As the men near the island, water rations grow low and have to be cut; desperate dehydration sets in. Land is spotted on the 14th day, but there is nowhere safe to put in. The drinking water is now completely gone. A hurricane-force gale rocks and floods the boat. The men feel the end is near. But the next day they finally find a bay in which to put in.

The small boat encountered 80-foot waves.

- But the men’s journey is far from over. They find themselves on the opposite side of the island from the whaling stations. Shackleton decides to make an overland journey to reach them, an expedition never before attempted, and one that would take the men over steep snow-slopes and glaciers, jagged mountain peaks, and impassable cliffs. But first another delay—bad weather keeps the men from starting the march for ten days, an anxiety-filled time as their thoughts continually turn to the men left on Elephant Island.

The island of South Georgia was beautiful and forbidding.

- When the march begins, Shackleton as always breaks the trail for the other men, trudging through soft, knee-deep snow and across fields of ice. Without flashlights, the darkness hides the deadly crevasses until they are just upon them. Several times the men grow hopeful that they are almost there, only to realize they have gone the wrong way, forcing them to gloomily retrace their steps. For 36 sleepless hours the men march in search of the whaling stations, stopping only for meals.

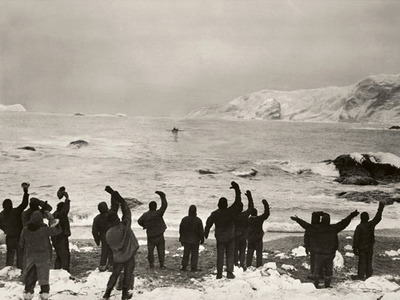

- Finally, Shackleton reaches the first signs of civilization he has seen in a year and a half. And still, the setbacks are not over. Shackleton is desperate to rescue the men on Elephant Island as quickly as possible. He makes three attempts to retrieve them, but each time the ship is forced to turn back because ice blocks the way. It takes a fourth ship and four months until Shackleton makes it back to Elephant Island, but he is greeted with the most rewarding sight of all: all 22 of the men he had left behind, alive, waving from the beach.

Hope. Progress. Crushing setback. Hope. Progress. Crushing setback. This was Shackleton’s reality for a year and a half. Such a string of endless disappointments might have made a lesser man want to curl up and die. But not Shackleton. Although he had moments where the weight of the situation sat heavily upon his shoulders, he would always shake off the gloom and resiliently move forward once more; his manly spirit could not be defeated.

This was true from his first setback to his last.

While the Endurance was trapped in ice, the ship’s captain, Frank Arthur Worsley, said of the man everyone called “The Boss:”

“Shackleton’s spirits were wonderfully irrepressible considering the heartbreaking reverses he has had to put up with and the frustration of all his hopes for this year at least. One would think he had never a care on his mind & he is the life & soul of half the skylarking and fooling in the ship.”

No matter what befell him, Shackleton remained of good cheer and always found reasons to laugh. Even on the soul-crushing boat ride to South Georgia, Worsley remembered him laughing. And on the arduous 36 hour hike to the whaling stations, Shackleton could still earnestly say, “laughter was in our hearts.”

And here is the mark of a real leader: the worse things got, the more cool and collected Shackleton became. Worsley remembered that Shackleton could sometimes be irritable when the going was good and he could afford it, “but never when things were going badly and we were up against it.”

How did Shackleton maintain his resilience amidst trials that would have made other men crumble? He concentrated not on the things that couldn’t be altered and weren’t under his control, but on what he could do.

After the Endurance sank, Worsley remembered that Shackleton was:

“bitterly disappointed, as sorely grieved as I was myself, and he let me get a glimpse of his mind when he said, sadly, one day: “It looks as though we shan’t cross the Antarctic Continent after all.” He paused, and then squaring his shoulders, added cheerfully, ‘It’s a pity, but that cannot be helped. It is the men that we have to think about.’”

And for the rest of the journey, that is essentially all he focused on, finding his strength in a service and a cause greater than his own ambitions.

A Leader Serves Those Under Him

“Shackleton’s first thought was for the men under him. He didn’t care if he went without a shirt on his back so long as the men he was leading had sufficient clothing.” –Lionel Greenstreet, First Officer

“How he stood the incessant vigil was marvelous, but he is a wonderful man…He simply never spares himself if, by his individual toil, he can possibly benefit anyone else.” –Thomas Orde-Lees

“Shackleton had a genius—it was neither more nor less than that—for keeping those about him in high spirits. We loved him. To me, he was a brother. The men felt the cold it is true; but he had inspired the kind of loyalty which prevented them from allowing themselves to get depressed over anything.” –FA Worsley

Equal in importance to Shackleton’s supreme resilience, was his care, almost obsession, for the well-being of his men.

Shackleton was ever concerned about his men’s morale. He understood that idleness quickly begets depression, and so he kept the men as active as possible, sending them out for vigorous games of football and hockey while the Endurance was trapped in ice. This is also why he chose to attempt the marches across the ice once the ship sank, wisely observing that:

“It would be, I considered, so much better for the men to feel that they were progressing—even if the progress was slow—towards land and safety, than simply to sit down and wait for the tardy north-westerly drift to take us from the cruel waste of ice.”

On the way to South Georgia, he assured that the men got regular meals and drinks of hot milk every four hours; the routine gave the men stability and something to look forward to. Worsley wrote:

“It was due solely to Shackleton’s care of the men in preparing these hot meals and drinks every four hours day and night, and his general watchfulness in everything concerning the men’s comfort, that no one died during the journey. Two of the party at least were very close to death. Indeed, it might be said that he kept a finger on each man’s pulse. Whenever he noticed that a man seemed extra cold and shivered, he would immediately order another hot drink of milk to be prepared and served to all. He never let the man know that it was on his account, lest he became nervous about himself, and while all participated, it was the coldest, naturally, who got the greatest advantage.”

He always thought of the needs of his men above his own, and he was always ready to sacrifice his own comfort for others. As Worsley put it, “It was his rule that any deprivation should be felt by himself before anybody else.”

When they sailed to Elephant Island, the expedition’s photographer, Frank Hurley, lost his mittens, so Shackleton gave him his own; when Hurley protested, Shackleton threatened to throw them them overboard. Hurley accepted the mittens, and Shackleton’s fingers became frostbitten. Yet he never complained. When they made land in South Georgia, the men were too exhausted to pull the boat all the way in. Therefore Shackleton decided to let the men eat and rest before finishing the job. But the boat had to be watched to make sure it did not float away. Shackleton took the first watch, and let the men sleep; he then took the second watch as well, which had been assigned to Worsley, because he was so grateful for the “Skipper” having brought them safely ashore. When the men marched over the island, Shackleton was in thin leather ski boots because he had given his warm, specially-made expedition boots to another man.

Shackleton thought of himself as the father of the men, and believed it was his responsibility to get every man out alive. This was a great weight to bear upon his shoulders, but he bore it stoically.

When the men landed on Elephant Island, Shackleton said to Worsley, “Thank God I haven’t killed one of my men!” Worsley replied, “We all know you have worked superhumanly to look after us.” To which Shackleton answered gruffly, “Superhuman effort…isn’t worth a damn unless it achieves results.”

A leader who serves and loves his men as Shackleton did, makes a sacrifice that is not simply altruistic, for such actions have the effect of forging the deepest loyalty.

When Shackleton prepared to leave on the voyage to South Georgia, he gathered his men, men who had just been through hell, and told them that the journey would be fraught with danger and had only the slimmest chances of succeeding. And then he asked for those who were willing to accompany him to step forward. Worsley recalled the scene:

“The moment he ceased speaking every man volunteered…On the island was still safety for some weeks. The boat journey promised even worse hardships than those through which we had but recently passed. Yet so strong was the men’s affection for Shackleton, so great was their loyalty to him, that they responded as though they had not undergone any of the experiences that so often destroy those sentiments. They were as eager to accompany him as they had been on the first of August, 1914, the day upon which we had sailed nearly two years before.

It must have been a great moment for Shackleton. There was a long and pregnant pause before he replied, and then he said only three words: “Thank you men.” I remember thinking that this was one of the finest and most impressive utterances I had ever heard.”

Sources:

South by Sir Ernest Shackleton

Endurance by F.A. Worsley

Related posts:

- Lessons in Manliness: Matthew Henson

- Wilderness Survival: Know Your Distress Signals

- Lessons in Manliness from Harry Houdini

- So You Want My Job: Antarctic Driller/Researcher

No comments:

Post a Comment